By Farhana Khalique

Word Factory Interview with David Rose, author of Interpolated Stories

Interview by Farhana Khalique

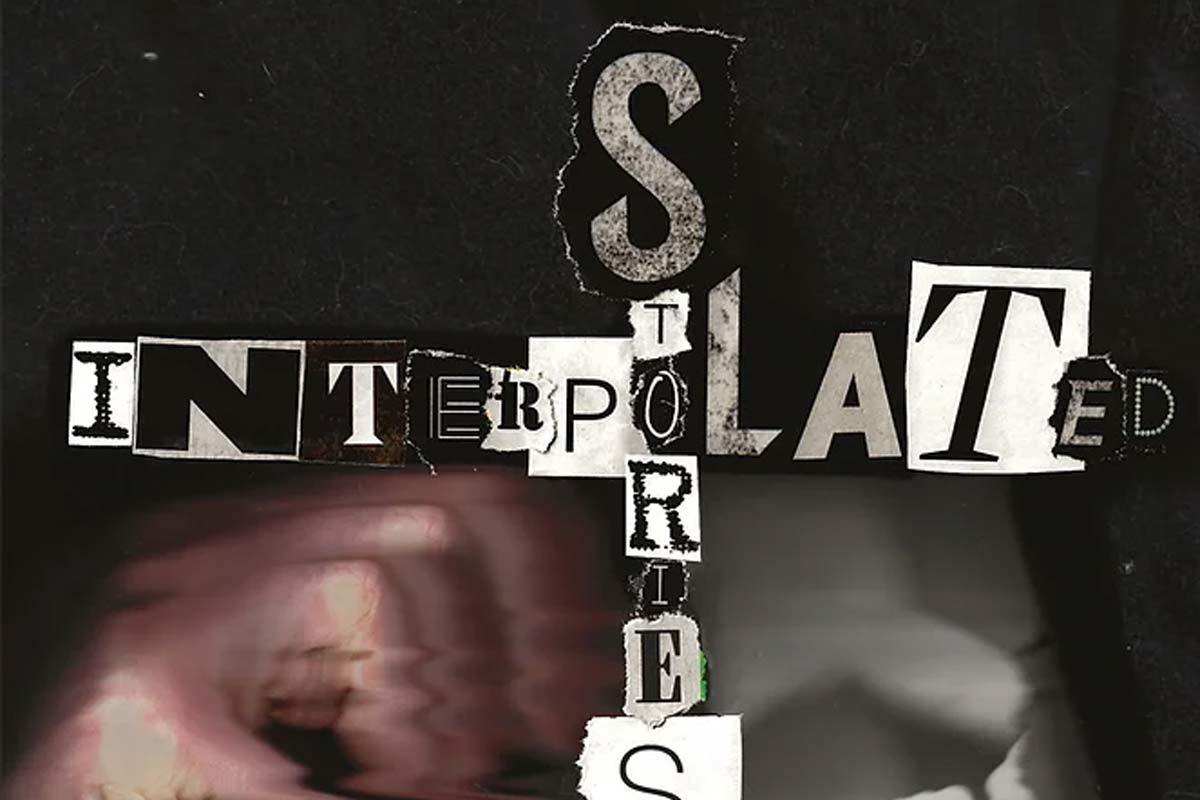

Interpolated Stories (Confingo Publishing, November 2022) contains several “interruptions” and commentary on the main narrative, or wider themes, or the act of writing. We spoke to David Rose about his process.

As a reader, I was briefly confused by the “rogue” question mark on page one of the first story, “Amongst the Corots”. Then, just as I was getting into this story about an illicit encounter in an art gallery, I turned the page and was intrigued by further rogue punctuation and additional words, and then… I was falling down a rabbit hole of meanings and possibility. Was that your plan, to lure the reader into following you through different rooms of possibilities, or were you experimenting for yourself?

I had no plan at all when I started on that story, certainly no planned collection. It was a purely subjective frustration I had while reading through an issue of a literary journal and feeling I had read those stories with slight modifications. That led to a realisation that my own work was no different – the too-easy lyricism, the worn-out tropes. So I took a very early story – the one you mention – and, as a writer/editor friend expressed it, “self-vandalized” the text with authorial comments. When I looked back on that, it struck me as a possible way forward. In the way, perhaps, that Jackson Pollock felt an obscure need to veil, even obliterate his language of symbols and typologies, which led him to his drip techniques. Or maybe like Duchamp and his work on glass, “The Bride Stripped Bare…”, which was dropped by a workman taking it to an exhibition, the resulting crack delighting Duchamp as adding a further dimension to the work.

I then took another story – I think it was “Smoke” – and this time used academic graffiti to disfigure and disrupt the narrative flow. It was when that story was published in Confingo in 2018 that the idea of a series, a collection of such “interventionist” stories was raised, by Tim Shearer, the editor of Confingo.

The collection felt like walking through an exhibition, pausing to read a plaque, or peer more closely at a detail, or step back and reflect on the bigger picture(s). At other times, the commentary reads like snippets of diary entries or overheard thoughts, e.g. in “Cobblers”. What was your process in terms of deciding what information to include and what to withhold?

As I reflected on the possibilities of this interventionist technique, I began to think of other forms of interpolation beyond authorial interjection or pseudo-academic discourse.

So, for example, in “Cobblers” we have the voices of the unborn children – an allusion to Eliot’s poem “Animula”. I wanted to see also if it would work with newly written texts, with interpolation built in rather than imposed. So we have the Biblical quotations in “Decrescendo” acting as ironic comments on Spinoza’s animate stones, and “Under the Plan”, the title of which comes from a TLS review of the eugenic movement in America in the early to mid-Twentieth century – a movement supported by Kellogg, hence his sales slogan, and one of the issues in the notorious and misunderstood “Scopes Monkey Trial”.

Several stories focus on (potential) acts of transgression. For example, getting caught canoodling while on the job (“Amongst the Corots” and “Smoke”), or committing a robbery (“Empire”), or assaulting a rude client (“Like It”). Why did you focus on such moments? Why did you leave some “cliff-hangers” or unresolved?

This related back to the previous question; acts of aggression, flash points, are moments when people transcend their everyday selves.

As for the cliff-hangers, that was a function of the interpolations, disrupting/frustrating the narrative flow. In some cases, that may work to improve the ending; the original text of “Munch…” for example, ended with him on Staines Bridge, with his hands to his head and screaming. Readers can decide which ending is better.

Several other stories seem light-hearted at first. However, there are hints of tragedy amidst the revelry. You make this blending appear seamless, but how important and difficult is it to do this in a short story? How much can you guide the readers’ feelings?

I take that the seamless blending refers to the original, uninterpolated versions of the stories. But that blending relates to life itself, which is neither pathos nor bathos, comedy or tragedy – those are just labels we apply or genres we use as articulation; at most, points on a spectrum. The particular blending – recipe, perhaps – comes naturally from the characters and the situation they find themselves in, and the theme of the story. For example, I wrote an early story about an opera singer, a contemporary of Caruso but who, unlike Caruso, turned down the opportunity to record his voice, and existed later as a footnote. I needed to make his character as lively and memorable as possible, so wrote it as comedy, but it was the saddest story I have written.

All this also relates to your point about guiding the reader. I don’t attempt to do so. In fact, a number of friends over the years have complained about being baffled by my stories, although pleasantly baffled (so they say). I believe, as a reader as well as writer, that meaning is more effectively conveyed when it’s just out of reach, off-stage, rather than explicated within the text.

The collection ends with “Edvard Munch Surveys Staines Bridge”, which brings to mind historical and mythological references, to bridges, to flowing rivers, streets and people, to lighting streetlamps, to the Dickensian/The Waste Land-style swirling, thickening fog… How interested are you in intertextuality and literary allusion?

Again, I find allusions come naturally, cross-fertilization often being the germ of a story. Munch’s work has been a constant source of interest and of narratives. In this case, the spark was the sudden connection between his image in “The Scream” – the figure on the wooden bridge (and the overall importance to Munch of wood – the number of woodcuts he made, for example), and a history I had been reading of Staines Bridge (which is very close to where I worked), which has existed as a river crossing since Roman times, and for most of that time, until quite recently, as a wooden bridge. The final element was Munch’s early painting “Evening on Karl Johan Street”, in which the crowd of people appear as if compressed into two-dimensionality, flattened against the plane, and the idea of Munch on a personal level being similarly flattened, by the loss of family members and friends; feeling the need for another dimension – of history.

I later discovered that he did in fact come to England – at least, to London – but that was in 1913; his work wasn’t exhibited here until 1936, and there is no record of him accompanying his work.

So the story grew from that web of allusions and historical coincidences, including references to Staines in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles.

You are an experienced and highly respected writer who has written several books, novels as well as short story collections, and have been featured in The Penguin Book of the British Contemporary Short Story, edited by Philip Hensher. Yet, you’ve mentioned that you came to writing “late” and that “these texts were born out of a sense of frustration” with contemporary short fiction. What advice do you have for emerging short story writers interested in form/experimentation, or anyone working on a collection?

I don’t really recognize that description – experienced, maybe, but highly respected? I’m hardly known in the literary Establishment. It’s true I came to writing late – in my mid-thirties, my debut story in the Literary Review appearing at the age of forty, my first novel at sixty.

But the remark about the sense of frustration relates to these specific stories in this collection; most of my previous work was, I believe, innovative but not experimental in this sense, and in a further series in which I applied other interventionist techniques, such as erasure, to existing texts.

And that frustration in retrospect deepened into a consideration of fiction’s ability to adequately reflect the modern world – a world of diverse and competing discourses and voices. What I found myself doing was engineering a collision of discourses – narrative, academic, personal – to see what fiction uniquely has to offer in that multiplicity. So my aims were quite specific in these stories.

In more general terms, I would encourage writers to experiment as much as possible, especially when starting out, and to discard whatever doesn’t work, as a way – the only way, really – to finding one’s own voice and themes.

I won’t ask you what your favourite book is in case that’s too hard to answer, but which book(s) have you reread the most? Is there anything you find particularly inspiring or helpful for unlocking your own creativity?

That would be hard – to narrow down my choice of favourite book. I can say that Eliot’s work has been a constant in my life, long before any thought of writing for myself. He died the year I left school, and I read the obituaries (I did a paper round at the time, and looked through the papers while delivering them). I later bought “The Waste Land and Other Poems” from W.H. Smith’s; deciphering those was my introduction to literary modernism.

With regard to fiction, two novels I can nominate objectively, having read them three times each, over three successive summers, after initially failing in both cases to get into them at all: Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game.

As for unlocking my own creativity, I suspect I may already have unlocked all that.

David Rose is the author of Vault (2011), Meridian (2015), Posthumous Stories (2013), and he is included in The Penguin Book of the Contemporary British Short Story (2018). Interpolated Stories is David’s latest collection, illustrated by Leah Leaf (Confingo Publishing, November 2022), ISBN: 978-1-7399614-6-6.

Farhana Khalique is a writer, voiceover artist and teacher from south-west London. Her writing appears in Best Small Fictions 2022, 100 Voices, This is Our Place, and more. She’s been shortlisted for The Asian Writer Short Story Prize and she’s a former Word Factory Apprentice. Farhana is also a submissions editor at SmokeLong Quarterly, a fiction editor at Litro, and she’s taught workshops with Flash Fiction Festival, Crow Collective, Dahlia Publishing and more. Find Farhana @HanaKhalique and www.farhanakhalique.com