Review by Catherine O’Neill

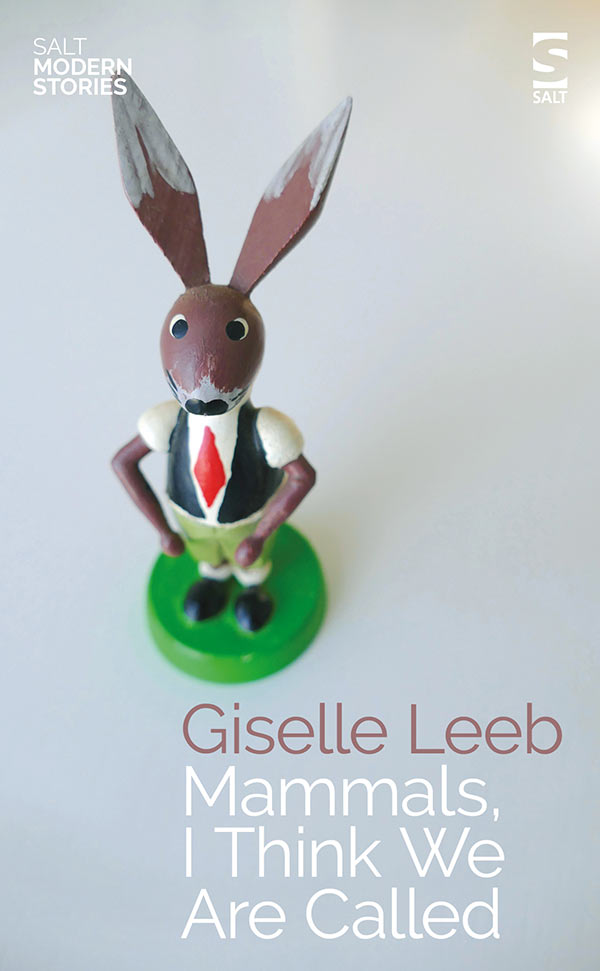

Giselle Leeb, Mammals, I Think We Are Called (2022)

In her debut collection, Giselle Leeb takes various vices of modern society and explores the potential consequences of humanity placing ego, ease, ‘progress’ and profit above all else. With striking characterisation and settings, Leeb forces the reader to observe that “eventually society will end” – as a doctor notes in ‘Dividual’. There are searing yet impassive depictions of desperate dystopias; detrimental scientific and technological ‘advances’; displacement; destruction; environmental discord; pain, as well as nostalgia for the world we presently inhabit. By illuminating humanity’s perverse rituals and excesses, the dangers we teeter on, our disconnect from nature and natural ways, Leeb viscerally portrays the destruction left for future generations.

Cruelty and exploitation of animals appear in several stories; Leeb comments on human disregard for the delicate balances of nature, as well as an ebbing away of compassion and empathy. Children across the globe are given synthetic gorillas – toys which are soon cast into forests; dogs are extinct; the mercury-poisoned sea is filled with repulsive limbed fish that humans once studied as potentially holding the secret to long life, but now feast upon:

You can’t blame it for being suspicious – I am a human, after all.

In the opening story, ‘The Goldfinch Is Fine’, a weatherman is numbed by the knowledge of an impending catastrophe yet clings to hope by watching, what he believes is, a live stream of a goldfinch. His world is precarious:

The neighbours’ children are playing behind their glass patio doors. Too exposed, he thinks.

He knows a deluge will soon hit but: “As long as the goldfinch is OK, it can’t happen, he tells himself.”

Leeb menacingly creeps through this familiar world and, with delicate twists, she reveals the dreadful death throes of society.

He can no longer wear clothing in colours the shades of deep water. And he has more chance of being seen in yellow.

Powerfully, Leeb subtly takes the much-repeated warnings of Climate Change and makes them mundane.

He couldn’t start to explain that ‘out there’ and ‘in here’ are phrases he wishes still had currency.

“It is becoming hard to predict anything”, making the weatherman at once obsolete and the last bastion of an illusion of control.

‘Grow Your Gorilla’ seems initially the fantasy of a child who is sure his gorilla will develop into a real-life gorilla. The synthesised gorillas are sold in their millions and duly discarded by children and parents. There is a dark humour that develops into a deep sadness as the child returns, when older, to find his gorilla was the one that did live:

I am so small, but I hold out my hands in hallelujah, I hold up my face, ready to be smashed…You come right up to me and put your face close to mine. You stare into my eyes. I notice that yours have deepened to dark brown.

In many of the stories, society is either dying or dead, as in ‘Drowning’ where the change was gradual and insistent: “If there had been less loss, he thinks, he may have noticed the changes more.”

In ‘When Death Is Over’, a couple live in a high-rise building. One is afraid to go to work and leave her depressed girlfriend alone with the potential that she will throw herself out of the window like many neighbours have done.

In the tower, the flats have windows facing outwards, and windows facing inwards too, to let in more light. But the hollow core is filled with darkness: debris, and some say bodies – bodies that were thrown, bodies that jumped from the fifty-fifth floor, bodies that block out the light.

The grimness and hopelessness are counteracted by a religious fervour:

The shepherds claimed they’d seen a falling man, a trail of stars behind him…They said that his leg was bent, then straightened, then bent – some thought he had been a ballet dancer – as if he couldn’t decide, or wasn’t comfortable.

Leeb suggests that, unlike Christ, the falling man’s death perhaps cannot lead to the redemption of humankind – the world is beyond saving. It is a grim yet chillingly familiar setting, with love being the only remnant of hope, though even that is under constant threat.

There is a nostalgia for a time before – the time that the reader lives in, a reminder that we have the power to enact change. In ‘Everybody Knows That Place’, a cyborg with human roots, “wants to go back in time, to be one of those people in camping trousers”. He pays for a trip to a ‘real’ campsite . Money is unnecessary and so is waiting, although they are both added to make the experience genuine.

…the new theme park has generated faint hints of excitement in him, a recognition perhaps of the ongoing need to connect with fully human roots. Something unexpected, not factored in. They still don’t understand it, but they’ve finally admitted defeat…

Leeb injects humour into this disturbing story with a memorable scene where the cyborg displays illogical human pleasure:

He finds himself listlessly plugging and unplugging his left eye from its socket. He’s started to wonder about this habit, and he’s also secretly proud of it – a nervous tic, really, something more pure human than cyborg. People remove them deliberately for cleaning, but he does it spontaneously, and this feels good.’

‘Thin’ and ‘Pain Is a Liar’ explore the unnatural limits of human suffering and idealism. In ‘Thin’, ten humans have been cryogenically frozen and thawed at some point in the future, a future where humans, look “like famine victims, but somehow healthy, with glowing cheeks and shiny hair”. The aim is for the ‘fat humans’ to reduce their body weight to one fifth of their current weight, “They were helping us to get thin so we could be like them”.

In ‘Pain Is a Liar’, Anton is experimented upon by the coterie. He aims to please them as they break his toes and fingers to gauge his reactions. The “experiments are voluntary”; he is part of “the herd” and can feel pain, unlike his pain givers.

Despite being so clever, they think that the members of the herd are all alike. They would never call themselves a herd. They are individuals.

Leeb makes political points: the herd are the working classes, the dispensable and partially human, as far as the unempathetic coterie view them. Anton’s desire to please outweighs his self-protective instincts. The herd are being thinned, sent to pasture, and seemingly powerless. It is a disturbing story that challenges the systems that exist in our society, shown as slowly and deliberately destroying humanity with a cruel hand.

Fantastical worlds are created that are repulsive and horrific. In ‘Wolphinia’ people drive into a mercury-poisoned sea, inadvertently killing strange creatures, wolphins, in the process. The wolphins have human qualities and once were seen as holding secrets about how to live a long life. Now the remaining humans feast on them. The government is small; just “2.3 percent” turned out in the election, and they dole out petrol to the people, “‘ride not riot” their slogan. Humankind is doomed, “nobody gives a shit since the babies stopped coming.”

The dark humour suggests civilization’s disintegration:

…I want the wolphins to know that I would never eat them – unlike some, I recognise their official person status. I’m not a fucking cannibal!

In ‘Barleycorn’ the dystopia is horrific. A woman dreams of being chased by a hairy man, as across town a pathologist, examining several severed body parts, sprouts hair all over his body. The story combines folk tales and a modern seeming New York to depict horrifically nature responding to its neglect.

‘Mammals, I Think We Are Called’ is a collection of short stories that stand together to howl out a warning. Leeb is clanging an environmental alarm bell for the ears of those that pursue personal profit, vanity, and hedonism, at the expense of the downfall of humankind and the poisoning of planet Earth. Leeb harnesses the power of prose to paint the perils of how, unchecked, humankind’s vices will lead us into places that are horrific, inhumane, doomed and stripped of the beauties of nature and wildlife. The collection is a potent mix of a screamed warning, expressed with a subtle eye for the creeping shifts into the twenty first century. These stories deserve to be read, to inform change at every level, and to act as a barrier to the humans that would still march further along this doomed path.

Catherine O’Neill is an author of short stories, poetry, plays, reviews, and is currently editing her debut novel, Sooty Blotch.

Catherine’s play Networking was staged at Live Theatre; she had a short story broadcast on BBC Radio; poetry published by Atrium; was shortlisted by Northern Gravy, and for Streetcake Magazine’s Experimental Writing Prize; her monologue Keep Granny’s Clock is available on YouTube. Catherine edits for Dishsoap Quarterly and established and edits Holmeside Writing for her writing

group.